I am writing every day. And so I can claim, I’m a full-time writer.

The reason is simple: before summer ended, I lost my job. In the quiet that followed, I did what I’ve always done to make sense of things—I wrote. What began as a way to steady myself became a way to live. Without meaning to, I became a full-time writer.

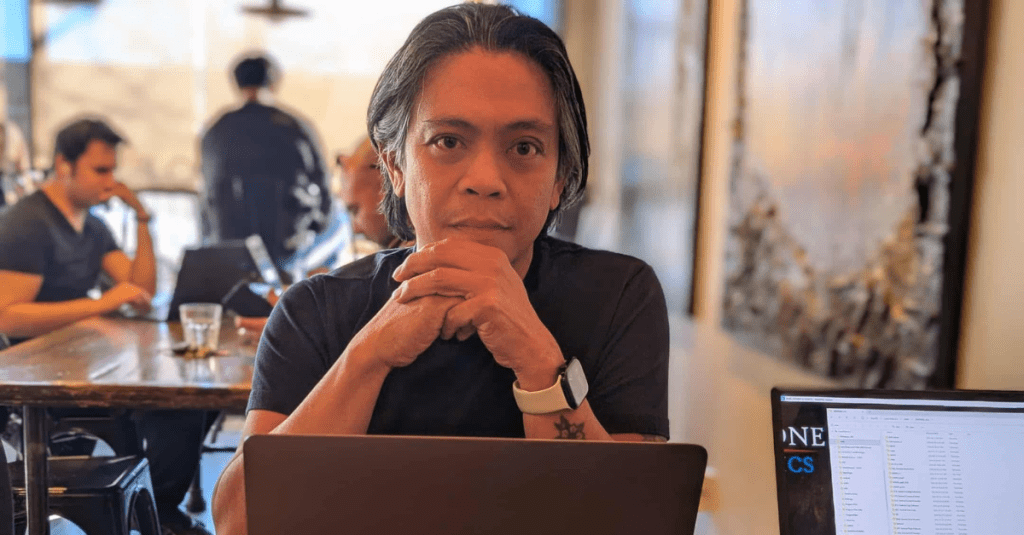

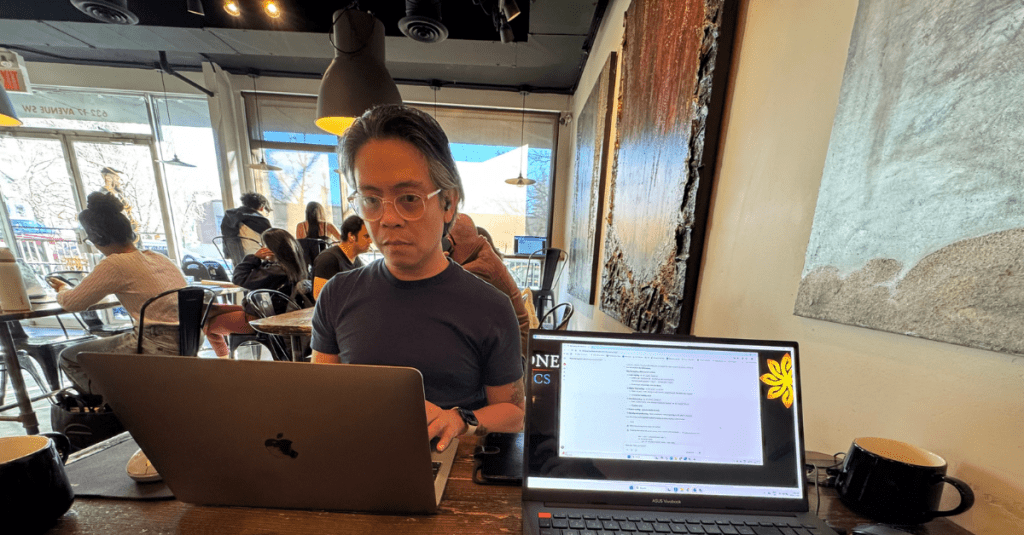

There was no romantic leap, no grand act of courage—just a gradual rearranging of days. The hours that once belonged to meetings and messages now belong to sentences. My mornings are for drafting, afternoons for revising, evenings for reading what I wish I’d written. On weekends, my husband and I pack up our laptops and find a coffee shop. He codes, I write. We call them writing dates—a quiet companionship of parallel passions, each of us absorbed in our work, together in the hum of doing what we love.

I’ve learned that discipline is another form of faith. Writing every day is a declaration that tomorrow will still need stories. It’s how I keep a kind of order—less about productivity than about presence. The blank page, unlike the office, makes no demands. It only waits.

Since then, life has reshaped itself in small but meaningful ways. I received another acceptance—this time from a U.K.-based anthology. My folkloric story Unkind Smiles found a home in Ginger and Smoke. My work with Salingpusa Magazine is in full swing after we released our first issue and began preparing our Winter 2026 edition. And in the process, I’ve connected with more Filipino-Canadian writers whose stories hum with the same tension of distance and belonging. These new kinships remind me that storytelling is, at its heart, a communal act—a way of saying we are here, across oceans and silence.

Still, the act of writing remains solitary. Some mornings, the words arrive easily, as though they’ve been waiting for me. Other days, every sentence resists, and I must coax it forward, patient as prayer. Yet even on the slow days, I’m aware that something is moving beneath the surface—that the page, blank as it seems, is listening back.

To live as a writer is not merely to produce text. It is to apprentice oneself to attention—to notice, to linger, to resist the rush toward certainty. It’s a way of turning absence into articulation, silence into shape.

I used to think success meant visibility—a byline, a paycheck, a performance review. Now I think it’s intimacy: how closely one’s inner life aligns with what appears on the page. The question I ask myself these days is no longer What do I do for a living? But, what does my living do for me?

Writing every day has become my way of answering. It reminds me that work can be an act of listening, that words can hold the weight of days.

Perhaps that’s what this season is teaching me—to trust that a life built around language can still be a life of integrity and structure. That meaning can be assembled sentence by sentence, like a house rebuilt after a storm.

I don’t yet know what the future holds—whether another full-time job will arrive, or whether this balancing act of contracts and creation will stretch longer than planned. But when I sit down at the desk each morning, I know this much: I am not unemployed. I am employed by wonder, by memory, by the stubborn desire to make sense of things.

And for now, that is enough.