Paris in late November smells of rain, stone, and bread warm enough to thaw your fingers. That’s the air we stepped into on November 23, beginning a short visit that felt like both a return and a reawakening. This is our third time in the city, yet Paris refuses to become familiar. Each visit feels like a different conversation with the same, stubbornly enigmatic friend.

We’re staying in Saint-Germain, where the streets glow a permanent shade of gold, even on grey days. We walked more than we planned—miles along the Seine, through museum halls, across palace grounds. Paris demands movement. It wants your feet, your lungs, your willingness to follow wherever its small wonders lead.

And along those walks, I noticed something that irritated me more than I’d like to admit: people still smoke everywhere. The old Parisian haze. As a former smoker, I found myself both repelled and strangely grateful—proof that I’ve shed a life I no longer want.

Scenes from a short return

One of our first walks was along the Seine, that patient green river carrying centuries of unspoken things. We revisited Notre Dame from the outside. The scaffolding is coming down, the stone emerging again—a slow, public healing that feels almost intimate to witness.

At some point, inevitably, we found ourselves at the Eiffel Tower. It doesn’t matter how many times you’ve seen it—it insists on being part of your Paris. This was our third visit in our three trips, and still the Tower felt absurd, beautiful, defiant. It exists for no reason other than to be looked at. I admire that kind of unapologetic presence.

We visited the Musée de l’Orangerie for the first time. Monet’s Water Lilies live in calendars and mugs back home, but standing in that oval room felt like being held inside colour.

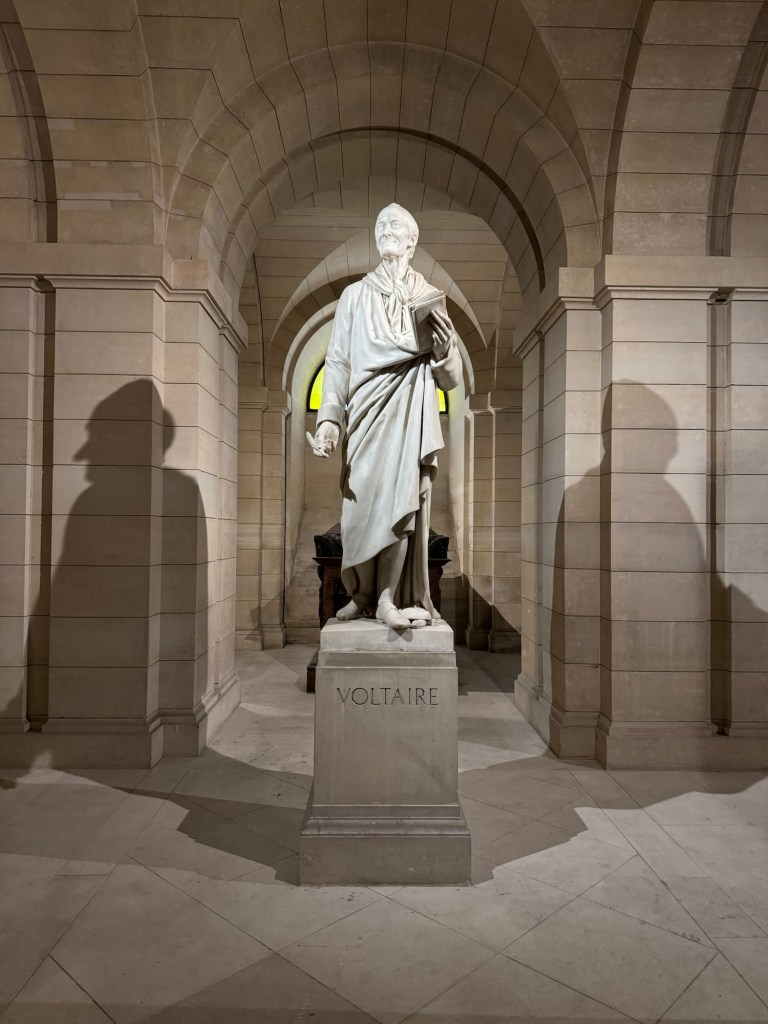

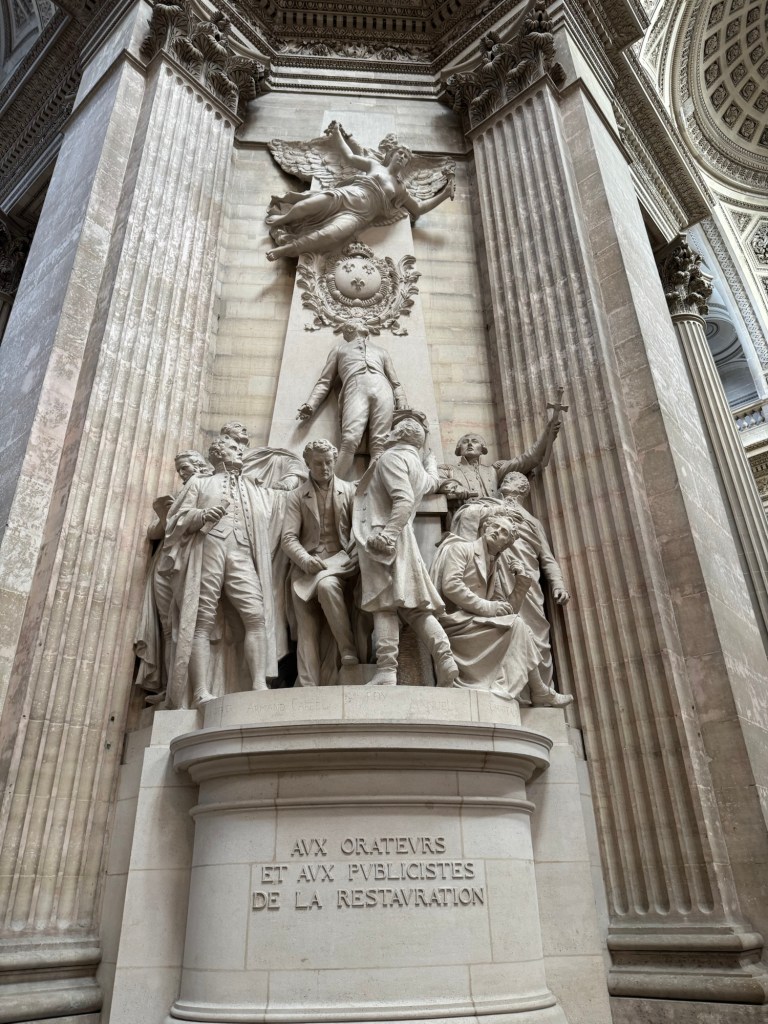

At the Pantheon, the grandeur was predictable; the emotion wasn’t. The crypt—Hugo, Voltaire, Rousseau—felt like the bedrock of ideas. Robert Badinter’s memorial hit me unexpectedly, a quiet testament to courage.

Orsay before opening, Versailles in the afternoon

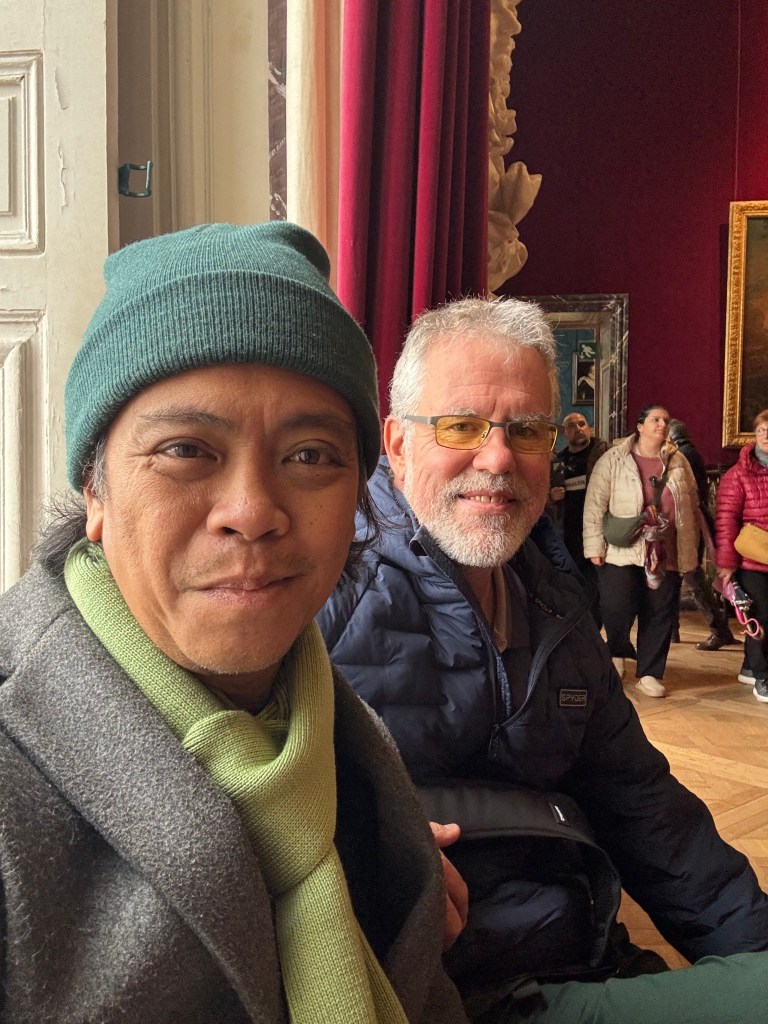

We reached the Orsay an hour before it opened—the closest you can get to having a museum to yourself. There’s a particular kind of anticipation in those moments, in being among the first to enter. The Impressionists felt both familiar and newly alive, their colours almost humming against the cold outside.

Versailles later in the day was overwhelming in a way that bordered on punishing. Rooms of gold, mirrors that multiply you, ceilings that refuse to be contained in a single glance. It wasn’t just beautiful—it was exhausting. By the time we reached the gardens, the ground had turned to mud and the rain had returned, a thin, persistent drizzle clinging to everything. I didn’t find solace there. I didn’t have the energy to explore, to marvel, or to pretend I wasn’t tired. I simply felt the weight of the place—the cold, the damp, the fatigue of having walked too much in too short a time.

Paris gave us wonder. Versailles reminded me I have limits.

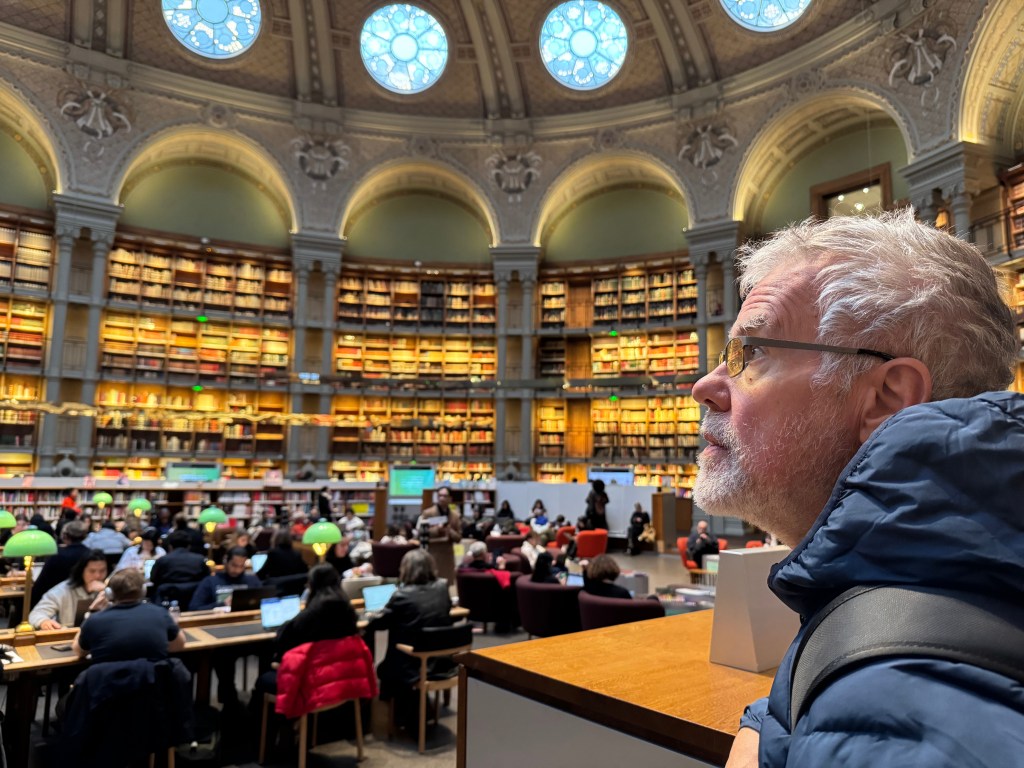

Ending in the Oval Room

We closed our visit in the Oval Room of the Bibliothèque Nationale—an architectural devotion to silence, geometry, and thought. The room feels like a breath held in perfect symmetry: a long, glowing ellipse of books rising in tiers, green lamps lit like soft stars, the kind of hush that isn’t imposed but shared. It’s the kind of silence that lets you listen inward.

Sitting there, I felt surrounded not only by the archive but by a different kind of presence—Levinas, Beauvoir, Sartre, Derrida, Foucault, Merleau-Ponty. Not because they worked at these exact desks, but because Paris still carries their questions in its air. Their voices linger in its streets, cafés, and universities, in the intellectual hum that never fully leaves the city.

These were the thinkers who once made Paris a laboratory of the mind, who turned cafés into seminar rooms and arguments into public events. Their ideas shaped how I write, how I look at the world, how I understand the self and the Other, the fractures and reconciliations inside relationships. In that oval room, I felt something quiet open in me—a reminder that thought has geography, that ideas come from bodies in places, not just books on shelves.

And I realized, as the rain tapped faintly on the skylight above, that I want to come back one day not just as a visitor but as a pilgrim. To trace the city as they would have known it: the cafés where Beauvoir drafted her pages, the Left Bank streets where Sartre lectured without permission, the halls where Merleau-Ponty wrote about embodiment, the libraries where Foucault bent language into new shapes.

Not to worship them—never that—but to inhabit the places where thinking once lived like breath.

The Oval Room felt like a beginning disguised as an ending. A quiet invitation.

Leaving, again

Today, we leave for Berlin. Three days in Paris is a fleeting thing, barely enough to settle into its rhythm. Yet it was enough: to remember wonder, to irritate old ghosts like cigarette smoke, to stand inside rooms built for kings and rooms built for silence, to feel the city tug at the boy I once was—the one in Calauag tracing Paris on a page.

We’ll return. Paris has a way of making sure you do. It’s not finished with us yet.