We arrived in Berlin after an eight-hour train ride from Paris—legs stiff, stomachs growling, minds foggy with travel. It was already dark. The air was cold and wet enough to cling to our clothes. But then we stepped into a Christmas market near our hotel, and the whole city seemed to shimmer awake. Warm light on wet cobblestones. The scent of cinnamon and frying dough. Children running between stalls. Music drifting through the night.

It was our first night of three, and Berlin greeted us with the same contrast it always holds: shadow and glow, sorrow and celebration.

I knew immediately how different this visit would be from my first one in 2023.

Back then, I came alone. I cycled everywhere—fast, restless, trying to outrun my own emotional capacity. I visited memorials without pauses, museums without breaks. I took everything in without someone to share it with, no one to say, “Let’s sit down for a moment.” I didn’t realize then that grief sits differently when there’s no one beside you to absorb its overflow.

This time, I walked.

And I was not alone.

Day Two—Stepping back into memory

The next morning was dry but grey—a steel-coloured sky hanging low, as if the city were wrapped in a single unbroken thought. We began at the Parliament grounds, where the Reichstag rises in sober grandeur. The glass dome still astonishes me: a democracy rebuilt with transparency made physical. I wanted Boyd to see this first—the architecture of accountability before the architecture of grief.

From there we walked to the Brandenburg Gate, its columns wet from the previous night’s rain, its stone catching whatever light managed to slip past the clouds. Berlin’s structures don’t merely hold history; they frame it, forcing you to stand inside its shape.

Then we reached the memorial I had been thinking about since we boarded the train from Paris:

the Memorial to Homosexuals Persecuted Under the Nazi Regime.

A simple concrete cube. A small window. A video inside on loop: two men kissing.

The first time, I stood there alone with my bicycle leaning beside me, feeling something inside me loosen and break open. I didn’t know why then.

But when I returned with my husband this time, I knew.

The memorial is understated, almost shy in its presence—but its intimacy is radical. A kiss shown in perpetuity where love was once punishable by imprisonment, torture, death. Queer survival rendered as softness. Queer existence honoured by tenderness.

This time, standing beside Boyd, I could feel the two Berlín trips overlapping: the self who came alone, and the self who has someone now. The one who cycled too fast, and the one who can walk slowly.

From there, the day deepened.

We walked to the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, descending into its concrete corridors. Then to Bebelplatz, where the empty bookshelves glow with absence. Berlin’s memory architecture is powerful because it is not afraid of voids; it doesn’t fill them in with comfort.

We stepped into the first museum of sort. While we were inside the Pergamon Panorama, the rain began. By the time we crossed to the Bode Museum, water streaked the windows, softening the city into a blur. At the Neues Museumand Arles Museum people shook off damp coats as we wandered through rooms of ancient fragments and quiet marvels.

Walking through Berlin with someone you love changes the emotional temperature of the city. The heartbreak is still there, but it becomes shareable.

We ended the evening the way we ended our first night: another Christmas market, the glow of lights insisting that joy has its place even in a city built on remembrance.

Day Three—Division, tenderness, and what the city doesn’t hide

Our third morning began at Checkpoint Charlie, which always feels like a stage set—history curated and re-enacted. But the rest of the day was anything but theatrical.

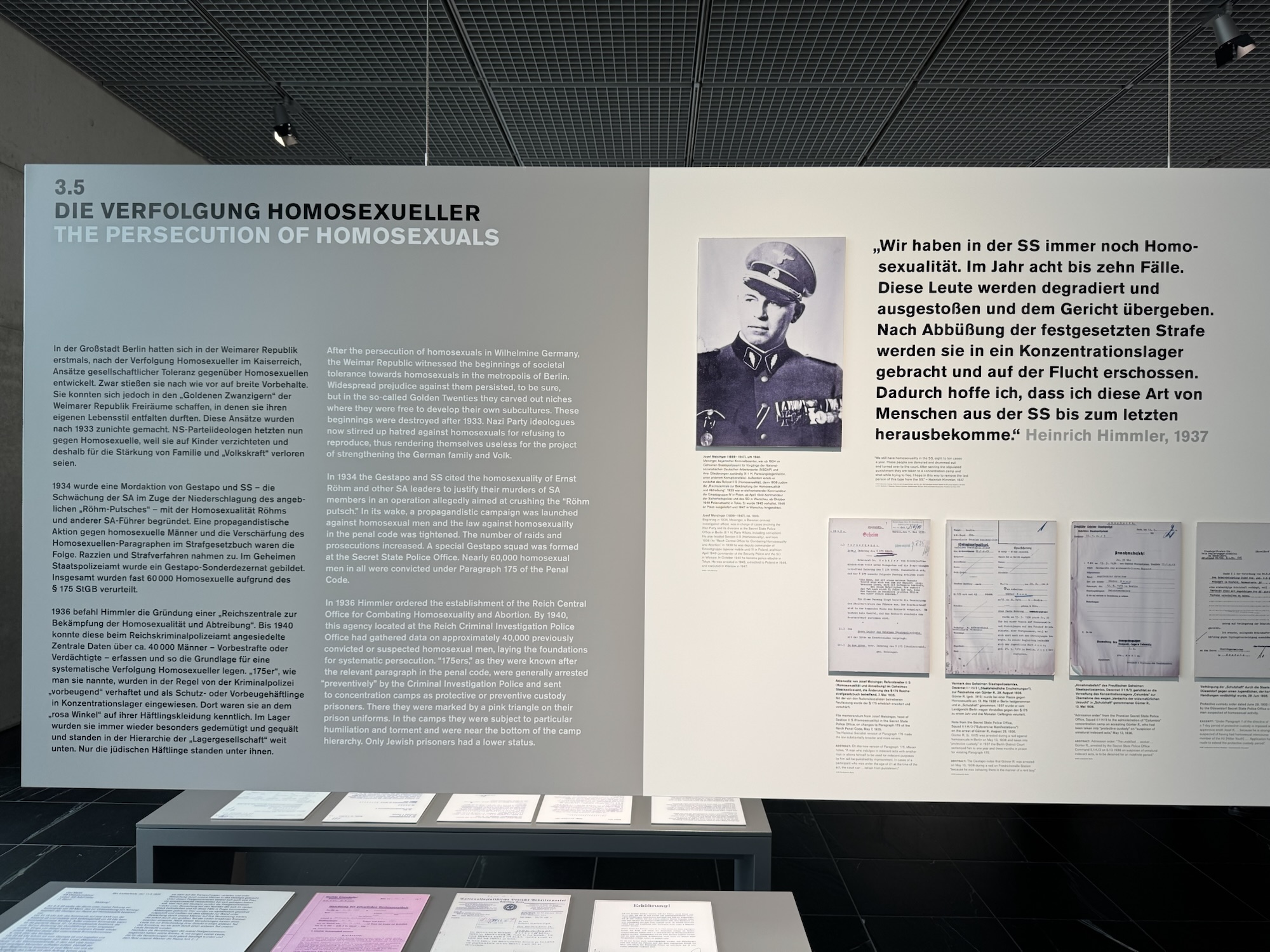

Our steps took us to the Topography of Terror, which sits on the site where the Gestapo and SS headquarters once stood. Even after two visits, the place still has a particular coldness—not just from the November air but from the architecture itself. It isn’t dramatic. It isn’t sculptural. It doesn’t aestheticize anything.

Instead, it exposes.

The outdoor grounds follow the contour of the old foundations—long concrete lines tracing the footprint of buildings where unimaginable decisions were made in ordinary rooms. You walk beside the excavated cellar walls, still scarred, still darkened by time, while a low glass-and-steel pavilion runs alongside them. The effect is clinical, almost surgical: Berlin refusing to bury the bones of its violence.

Inside, the exhibition is relentless in its simplicity.

No theatrics.

No inflated emotion.

Just documents, dates, correspondence, orders, faces.

A bureaucracy of cruelty displayed step by step.

What struck me on both visits—but more sharply this time—was how ordinary the people looked in the photographs: smiling in pressed uniforms, standing confidently at desks, pen in hand. They look like people you might meet on transit or in an office hallway. The horror comes not from the images themselves, but from the text beside them: the decisions they authored, the machinery they oversaw.

It’s the banality of evil laid bare.

No mythmaking.

No distancing.

Just history at its most uncomfortable proximity.

Walking through it with Boyd beside me changed the emotional temperature. When I came here in 2023, alone and on my bicycle, the exhibition felt crushing—a weight pressing forward from behind the glass. This time, I could breathe between the panels, pause, look away, return. It became not lighter, but more survivable.

And outside, the remnants of the Wall still stand—jagged, graffitied, refusing to be smoothened over—a reminder that history doesn’t end where you think it does. The ground between the Wall and the excavated headquarters becomes a corridor of two violences, held in one landscape.

On our way to the Berlin Wall Memorial, we passed the kinds of quiet, scattered presences you notice when you walk instead of race through a city: someone sleeping in front of a closed building, a tent tucked discreetly near the riverbank, another in a park where the grass was still wet.

Not clusters—just individuals, spaced out through the city like unspoken footnotes. Berlin remembers its past with meticulous care; its present, like every major city, holds people it struggles to protect. The contrast is impossible not to notice.

At the Wall, the wind moved like a blade. The cold seemed to seep up from the concrete itself. I had cycled here in 2023, the wind hitting my face as if trying to tunnel my past through the present. Walking this time slowed everything down. I could actually listen.

The East Side Gallery lifted the heaviness slightly—colour layered over trauma—though even the murals looked subdued under the grey November sky.

What changed between then and now

By the time we reached our final night, I understood what had shifted between 2023 and this return: I wasn’t carrying Berlin alone.

Walking instead of cycling let me feel rather than flee.

Having Boyd beside me made the sorrow more bearable, more human, more shared. Seeing unhoused individuals scattered across the city reminded me that history’s lessons don’t automatically solve the present.

And returning to that small concrete cube in Tiergarten—now with my husband beside me—anchored the entire trip.

It reminded me: I am not the person who came here in 2023. I don’t have to carry what I carried then. And I don’t have to carry anything alone.

Berlin hasn’t softened.

But I have.

Or maybe I’ve simply learned how to hold its heaviness with steadier hands.

When I return to Berlin—and I probably will—I’ll begin there again, at the queer memorial that remembers what the world tried to erase. A kiss, looping forever, refusing to disappear.

A reminder that history doesn’t just break us. Sometimes, it returns us to ourselves.