I noticed the padlocks even before we stepped foot in Cologne. As our train rolled across the Hohenzollern Bridge, they flashed past the window in a blur of colour—pink, brass, rust, red, an entire spectrum of declarations fused to metal. I didn’t know what to make of them then. Just an impression, a texture of the city, one of those things you file away without meaning to.

The city that kept its distance

Cologne was gentle but not eager. Warm, but not performative. It let us wander freely without insisting we understand it.

Take the Dom: the first thing that seizes your sightline when you emerge from the station. A cathedral so tall and intricate it looks like it might puncture the low late-November sky. We tried three times to see its details—morning, afternoon, early evening. Always busy. Always a crowd thick enough to keep us moving along the perimeter.

There was no quiet moment to stand still with a gargoyle. No space to study a carving. We lingered, necks craned, trying to follow the impossible verticality of its towers.

And I didn’t mind. Some places aren’t meant to be conquered in two days. Some beauty is meant to remain incomplete.

The temptation of chocolate and the discipline of the diabetic

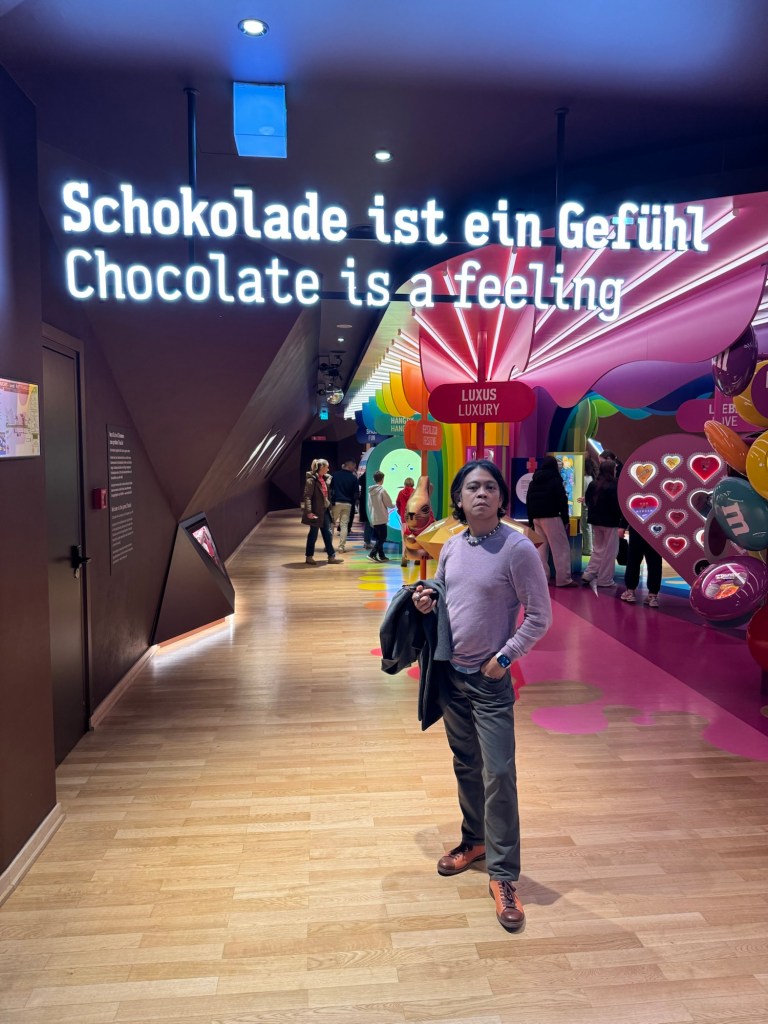

The Lindt Chocolate Museum hit us before we were through the door—warm, sweet, dense enough to taste. Boyd and I exchanged a look. We knew what we were walking into.

“This is a torture chamber for diabetics,” I whispered as we passed the chocolate fountain, a three-meter cascade of molten dark chocolate thick enough to have its own gravitational pull.

But we were prepared to be disciplined. We’d let scent be enough. We’d admire from a distance. We’d be good.

Then I saw the shop.

Rows of chocolate bars in jewel-bright wrappers—raspberry, hazelnut, salted caramel, mint. I started scanning labels anyway, looking for anything that said sugar-free, knowing it was probably pointless but unable to stop myself.

Boyd was doing the same thing on the next aisle.

A staff member noticed us searching. “Can I help you find something?”

“Do you have any sugar-free chocolate?” Boyd asked. “We’re both diabetic.”

She thought for a moment, then reached into the middle of the display—right between the milk chocolate with almonds and the dark chocolate with sea salt—and pulled out a single bar.

One hundred percent cocoa. No sugar, no sweetener, no compromise.

“Oh, a bar of charcoal,” I said.

Boyd looked at it, laughed that small laugh that means of course.

The staff member smiled apologetically and put it back among the real chocolate, where it had been hiding all along. Camouflaged by everything we couldn’t have.

Around us, children ran with chocolate-smeared joy. A woman bit into a salted caramel and closed her eyes. The staff handed out samples—little rectangles of milk chocolate—and we walked past them with our hands in our pockets.

We stayed another twenty minutes, long enough to see the production line, the tempering machines, the history. Long enough to feel like we’d done the museum properly. At least the museum has exhibits explaining poverty and racism and the oh-so-delicious concoction.

But when we left, I was aware of what I hadn’t tasted. And the smell in my hair felt less like indulgence and more like evidence of something I’d been denied.

Ludwig: Where art asks you to wait

The Ludwig Museum offered a different kind of richness after the chocolate museum—calm, curated, a little challenging in the way modern art often is. We wandered into rooms that seemed to invite patience: nothing loud, nothing urgent, just art standing quietly, waiting for you to meet it halfway.

And then I found myself standing in front of a wall of Picassos.

Black and white compositions, sharp-edged and fractured. A few with slashes of yellow, green, red—colours that felt aggressive rather than inviting. Faces pulled apart and reassembled in configurations that my brain kept trying to correct, to put back into some recognizable order.

I stood there longer than I wanted to admit, waiting for something to happen. Waiting for the click of recognition, the moment it would make sense.

It didn’t come.

I remembered liking Picasso once. Years ago in Barcelona, I’d seen his early work—the paintings before he started breaking everything apart. Those were tender, almost classical, full of clarity. I understood them. I understood him then.

But these—I didn’t know what to do with these.

Boyd came to stand beside me. We looked together in silence for a moment.

“I really don’t understand it,” echoing me.

There was relief in that. At least I wasn’t alone in my confusion.

Around us, other people moved slowly through the gallery. A couple stood in front of one of the paintings, heads tilted. A woman with a notebook wrote something down. I found myself wondering if they were pretending, if they’d learned the language of appreciation without actually feeling it, or if they genuinely saw something I couldn’t.

“Art’s subjective,” Boyd said, still looking at the paintings.

“It is,” I agreed.

And it was true. It is subjective. Not everything has to speak to everyone. But standing there, I couldn’t shake the small discomfort of not getting something I felt I was supposed to get. The gap between Picasso’s reputation and my indifference felt like a failing, even though I knew it wasn’t.

We moved on to the next room. The Picassos stayed on the wall, still fractured, still inscrutable, still waiting for someone else to meet them halfway.

Crossing the bridge: The locks, again

When we left Ludwig and crossed the Hohenzollern Bridge on foot, the padlocks greeted us again—no longer a blur through train glass, but a physical wall of metal and memory stretching along both sides of the railing.

Up close, they were strange. Thousands of them layered over each other, some clipped onto chains hanging from older locks, creating dense clusters of declarations. Some were clearly decades old, their engravings faded into anonymity, the metal spotted with rust. Others were bright and new, still carrying the optimism of recent commitment.

I kept my hands in my pockets.

Some of the older ones were rotting, metal corroded by years of rain and river air. I thought about how many hands had touched them—strangers running their fingers over other people’s promises, tourists taking photos, people like me trying to understand. I didn’t want to touch them.

Boyd was looking too, reading the ones he could make out. Initials. Dates. Hearts drawn in permanent marker. Some elaborate, some impulsive. A few were heartbreakingly earnest: J + M Forever scratched into brass.

“Do you get it?” I asked.

“Not really,” he said.

Neither did I. Why lock love to a bridge? Why leave it to weather and strangers and time? What does a padlock prove that a promise doesn’t?

Ahead of us, a couple was attaching a new lock to the railing. A friend—maybe a relative—was photographing them, directing poses. The woman held the lock while the man threaded it through a link in the chain. They were both smiling, performing the ritual with the seriousness of people who believed it meant something.

I watched them toss the key over the side into the Rhine below. A small splash I couldn’t hear but knew was there.

I felt cynical watching them. Cynical about the performance, the certainty, the idea that metal could hold anything as unstable as love. But then—to each their own. It meant something to them. That was enough, wasn’t it?

Boyd and I kept walking.

The padlocks stayed behind us, layering themselves into history, rusting into permanence or impermanence or whatever state exists between the two. I didn’t understand them. I didn’t need to.

Some things people do because it matters to them, not because it makes sense to anyone else.

Wind, water, and the practice of humility

We continued along the Rhine, and the wind decided to humble me. It whipped my hair directly into my mouth, repeatedly and with enthusiasm, as if the city had decided that my vanity needed a lesson.

I have whole sequences of photos where I am essentially eating my own hair. Not elegant. But honest.

The river moved at its own unhurried pace. Barges glided by without urgency. People strolled, not hurried. Everything felt proportioned. Human in scale. A relief after the intensity of Berlin and the restless beauty of Paris.

The city that expected nothing from us

Cologne has none of Berlin’s emotional gravity, none of Paris’s theatrical beauty. And yet, it offered something I didn’t find in those places: steadiness.

A place content to be itself, and content to let you be yourself.

We noticed occasional signs of people sleeping rough—a tent by the riverbank, someone in a building entrance, another figure tucked beside a park’s stone wall. Sparse, quiet reminders that no city is only its postcard angles. Cologne wasn’t trying to hide anything. It wasn’t trying to impress, either.

Maybe that’s why two days felt enough. Cologne didn’t require anything more from us. It met us where we happened to be—curious, tired from trains and museums, grateful for gentler days.

Leaving Cologne

On our last morning, I looked at the Dom one more time from a distance. We never did manage to get close enough to study its details. I still don’t know what the gargoyles look like.

As our train pulled away, the bridge appeared once more—the padlocks blurring back into abstraction, returning to the place where they first found me.

I still didn’t understand them. But my hand went to the window anyway, as if I could touch what I couldn’t name.