It had been more than a year since my husband and I last went to the cinema together. Not the distracted kind of watching—paused scenes, phones within reach—but the deliberate ritual of leaving the house, buying tickets, and sitting in the dark with strangers, allowing a story to have us fully. Somewhere between work, exhaustion, availability of films in various subscription portals and the long aftermath of recent years, that habit quietly slipped away.

I decided I wanted to see Hamnet after watching Chloé Zhao speak at the Golden Globe Awards. Accepting the award for Best Motion Picture — Drama, she referenced something Paul Mescal had said to her earlier: that making Hamnet taught him the importance of being vulnerable enough to be seen for who we are—and for who we ought to be. Of giving ourselves fully to the world, even the parts of ourselves we are ashamed of, afraid of, the parts that are imperfect, so that the people we speak to might fully accept themselves too.

That thought stayed with me. Not vulnerability as performance, but vulnerability as discipline. As offering.

Hamnet is a story about grief, but not the kind that announces itself loudly. It is grief as atmosphere. As weather. As something that settles into the body and quietly rearranges daily life. Watching it unfold on screen, I felt how familiar that texture was. This wasn’t grief as plot. This was grief as condition.

Sitting in the cinema, I began thinking about my own writing practice—about how I approach grief and trauma on the page. Earlier in my life as a writer, I was often tempted to make pain legible too quickly: to explain it, contextualize it, resolve it. I mistook clarity for honesty. Resolution for depth.

But grief resists efficiency. It doesn’t move in straight lines. Often it arrives sideways—in a hesitation of the body, in a memory that misfires, in an ordinary moment that suddenly becomes unbearable for no clear reason. What Hamnet does so well is honour that unruliness without turning it into spectacle.

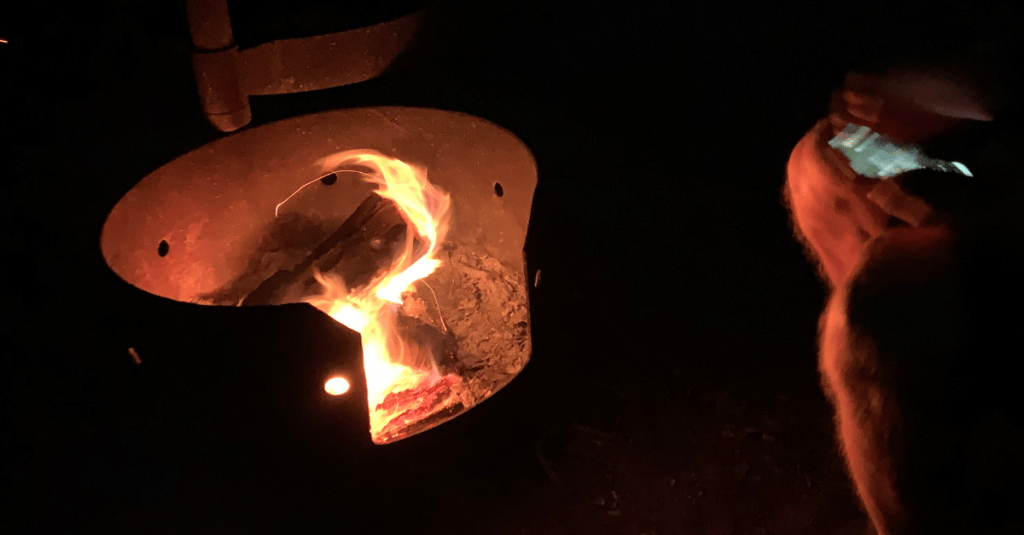

Recently, an editor who read one of my short stories put language to something I’ve been learning slowly. “You didn’t burn the house,” she said. “You contained it to a barrel. That’s discipline. That’s restraint.” The comment stayed with me because it affirmed a choice I once worried was a limitation. I now see it as an ethic.

Restraint is not absence. It is care. It asks the writer to know what not to say, where to pause, when to let silence do the work. Especially when writing about trauma, restraint becomes a moral stance. Not every wound needs to be flung open for proof. Not every fire needs to take down the whole house.

In my recent work, I’ve become less interested in the moment of impact and more attentive to what lingers. How grief alters language. How it settles into muscle memory. How it can be inherited, misremembered, or disguised as something else entirely. I’m drawn to accumulation rather than climax, pressure rather than release.

The cinema sharpened this understanding. There is something powerful about shared quiet—about sitting with others who are also not looking away. You feel it when a room collectively holds something fragile. No one speaks, yet the air changes. The grief on screen doesn’t belong only to the characters; it brushes up against your own.

When the film ended, my husband and I didn’t rush to talk. We let the silence come with us into the night. It felt like the right response—not to summarize, not to extract meaning too quickly, but to let the residue settle.

I left the cinema thinking about how grief asks to be written: not as an event, but as a presence. Not as something to conquer, but as something to listen to. What Hamnet offered me wasn’t answers, but permission—to be vulnerable without exhibition, to be restrained without being closed, to give myself fully to the work, even the imperfect parts.

Sometimes returning to the cinema isn’t about the film alone. Sometimes it’s about being reminded how to sit with what hurts—and allowing that discipline to follow you back to the page.