This short fiction is the contest winner for Milk Bag Magazine’s issue 1.4 The Long Night. It was originally published in the magazine in December 2025.

The road to Rocky Mountain House is a lesson in bad reception.

Halfway from Edmonton, my voice cuts out—first the Bluetooth, then the signal. I’m listening to The Crime Line, the podcast I promised my producer I’d “keep feeding” during bereavement leave. The irony lands hard. I’m driving toward my father’s death with my own voice narrating murder through static.

The last stretch of highway smells like cedar and smoke. The fire ban was lifted last week, but Albertans treat rules as suggestions. I pass a ditch fire that looks contained until it isn’t. Wind kicks up, carrying sparks. The province is full of controlled burns that never stay controlled.

The cabin appears where the trees thicken and the asphalt gives up. My father bought it after retiring from the RCMP—said he wanted quiet. We both knew he couldn’t live without a place to file things.

Now it’s mine. The pension, the debts, the ghosts.

Inside: gun oil and mould. The power’s off. Cold air bites. On the table sits a neat stack of boxes marked Case Files—Do Not Destroy. Classic Ray Calder. The man retired from investigating crime and still left a crime scene behind.

I drop my bag by the door and set up my camera—old habits. Framing the shot, I think of all the stories I’ve opened this way: clean establishing image before the blood or the tears. I can almost hear my voice-over: “When people die, they leave two kinds of evidence—the kind that tells the truth, and the kind that makes a good story.”

I light the fireplace. The flame catches slow, reluctant. Shadows ripple across the boxes. I flip one open: loose files, photos, a reporter’s notebook—not mine, but close enough. Each page smells faintly of smoke.

At the bottom, a cassette in a clear case. My father’s handwriting on the label: Leduc, 1998.

The year I turned twelve. The year my first girlfriend disappeared.

I slide it into my coat pocket before I can think too much. Outside, wind rattles the trees. The flame in the fireplace pops and dies.

By the time the fire holds, I’ve half-emptied the first box. The files are older than me — yellowed carbon copies, handwritten case notes, press releases stapled crooked. Some are marked solved, others pending. Most have no ending at all.

I recognize a few names. Rural crimes from when I was still in school—a farmhouse shooting near Wetaskiwin, a body found in a drainage ditch north of Leduc. The kind of stories I’ve reported on years later, quoting “former RCMP sources” who were really my father’s drinking buddies.

At the bottom of the stack: clippings of my own work. Calder’s kid exposes cold case cover-up. The headline from my first big TV segment. He’d circled the title in red pen and scribbled beside it: Speculative. No confirmation from detachment. Sloppy attribution.

Underneath, in smaller letters: You can do better, Tess.

The name hits like a bad aftertaste. Nobody’s called me that since before the braces and the eyeliner. I hold the page too close to the fire, watch the ink ripple, then pull back. I don’t want the smoke alarm going off—or maybe I don’t want to erase the evidence yet.

Next folder: photos of a missing-persons case from 1998. A teenage girl in a jean jacket, standing in front of a blue pickup. Her smile is hesitant, eyes squinting against sun. The handwriting on the back says Leduc, 1998 — the same as the cassette in my pocket. I don’t need to flip the photo to know who she is.

Samantha Bell. Sam.

My first girlfriend. The one I told everyone moved away.

I slide the photo under a notebook before I can see her face again. I try to focus on the papers—old interviews, witness statements, timestamps. My father’s block letters march across every page, relentless. There’s a notation near the bottom: case unresolved—family closed file prematurely.

Then, in red pen: Child interference? Investigate Calder link.

My breath catches. I read it again. Same words. Same handwriting.

He’d underlined Calder link. Twice.

The fire gives a low pop, throwing sparks across the grate. I shut the box, hard. The sound echoes louder than it should.

Out of reflex, I pull my phone from my pocket and tap the recorder app. The red circle pulses—Recording. I hear my own voice, steady and practiced, like I’m back in the studio: “This is Therese Calder, host of The Crime Line. What happens when the story isn’t someone else’s?”

Silence. Just the hum of wind through the chimney.

I close the app. I can’t decide if I’m gathering notes or building an alibi.

The knock comes midafternoon, when the sun slips behind the ridge and the light inside turns the colour of tea left too long. I’ve just started the second box—autopsy reports, water-damaged and curling—when the sound jolts through the room.

Two knocks, a pause, then one more.

I open the door and find a man standing on the step, hands shoved deep into a parka that’s seen too many winters. White stubble, eyes the pale blue of thawing ice.

“Therese Calder?” he says. Not a question so much as a confirmation.

“Yes.”

He sticks out a hand. “Gord Reimer. Your dad and I served together back in Red Deer. I heard you were in town.”

I hesitate before shaking. His grip is dry, the handshake short. He peers past me into the cabin—the boxes, the fire still burning low.

“Cleaning up?”

“Trying to.”

He nods like he already knows what’s in them. “Ray was always a hoarder of evidence. Said you never knew which scrap of paper would solve a case.”

I give him a polite smile. “Some people never retire.”

“Not your old man. He was asking about that Leduc file again, just before…” Gord gestures vaguely toward the trees. “You know. Said he thought the wrong man went away.”

My stomach tightens. “I didn’t know he was still working anything.”

“Working? Maybe not. Obsessing, sure. He came by the detachment last year, poking through the archives. Said it was personal.”

The word personal hangs between us like a wire about to snap. I cross my arms, keeping my voice light. “He didn’t mention it.”

“He never did.” Gord’s gaze shifts toward the fireplace. “Smells like birch. Always hated how he’d burn pine—sap gums up the flue.”

“I’ll keep that in mind.”

He smiles, thin and tired. “You sound like him, you know. The tone.”

I laugh, brittle. “Occupational hazard.”

He takes a step back, glances toward the shed. “Just keep an eye on the stove pipe out there. Smoke carries far in these woods.”

When he leaves, the air feels heavier, like the cabin exhaled something it shouldn’t have been holding.

I notice the faint scent of burning—not from the fireplace. Outside, a thread of smoke curls up from behind the shed, lazy and grey.

The smoke is faint but deliberate—a thin, straight column rising from behind the shed, not drifting like damp leaves would. I grab my coat, step into the cold. The ground crunches underfoot. The air smells like wet wood and something older, like old sweat baked into canvas.

The padlock on the shed is new, black steel, not rusted like the hinges. I try the keyring from my father’s desk—none fit.

Inside my pocket, the cassette presses against my thigh like a small pulse.

I find a crowbar by the firewood stack and jam it under the latch. The metal gives with a sound that feels louder than it should, a dry scream that sends crows shrieking from the trees.

Inside: a workbench, two chairs, stacks of VHS tapes in cracked cases. Everything smells of char—faintly chemical, like burnt plastic and solvent. The single window is blacked out with garbage bags.

On the table sits a burn barrel—rusted steel, still warm. Inside, something smoulders: shredded paper, a corner of a photograph curling at the edges.

I pick up one of the tapes. The label says Evidence—Unsolved (Keep Copy).

Another: Case Interviews / Audio – 1998–1999.

At the end of the row, a dictaphone. The same model I used for my early field reports, back when I still transcribed everything myself.

I press play.

Static. Then his voice.

Calm, methodical, unhurried.

“State your name.”

“Samantha Bell.”

“Tell me what happened that night.”

I freeze.

The girl’s voice trembles. I know it. The cadence, the way she swallows consonants—small-town Alberta, too many unspoken things between words.

Then I hear something else layered under the static—my own voice.

“Samantha Bell vanished on June twelfth, 1998, last seen leaving a gas station off Highway 2A…”

It’s my narration, word for word, from The Crime Line: Episode 12—The Girl from Leduc.

He’d recorded over it—or maybe I had. The two of us talking over the same ghost, competing for control of the story.

I hit stop. My hands are shaking.

I scroll back a few seconds, press play again.

“Do you know who was there with you, Sam?”

“He said not to tell—”

“Who?”

“—you, Mr. Calder.”

Then silence.

I rewind, but the tape sputters, chews itself. The sound of tape tearing is almost relief.

On the workbench, beside the barrel, a small notebook lies open. My father’s handwriting, dense as a police report: Evidence inconclusive. Witness unreliable. Protect family interests. Underlined twice: Don’t let Tess find this.

The heater in the cabin clicks on in the distance, or maybe it’s the wind through the stove pipe. The world feels thinner.

I close the notebook, drop it into the barrel. It doesn’t catch. The paper smoulders, refuses to burn.

From nowhere, or from memory, his voice again—deep, amused, close: “Some things you don’t bury, Tess.”

I turn, expecting the door to be open, someone standing there. Nothing. Only the smell of smoke, the sound of crows settling again.

I press stop on the recorder and slip it into my pocket. My hand smells like ash and cold metal.

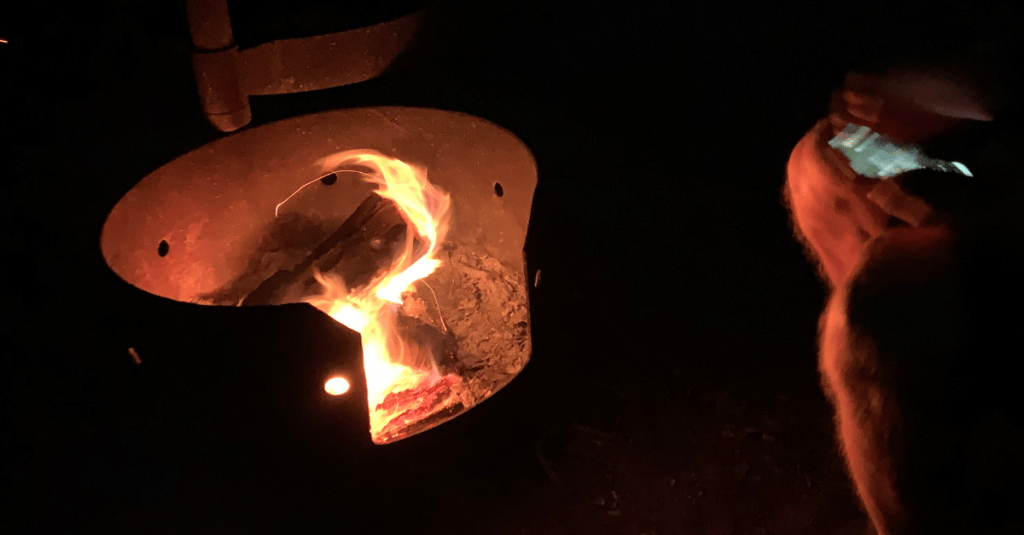

By the time I drag the burn barrel outside, the sky has folded into charcoal. The snow line glows faintly in the dark, a horizon made of ash. The wind gnaws at the treetops, then drops off, as if the whole forest is waiting for me to strike the match.

I build the fire the way my father taught me—small kindling first, then larger pieces laid like ribs. “You start gentle,” he used to say. “Fire’s a living thing. It needs to trust you.”

I pour in fire starter fluid anyway.

The first whoosh of flame tastes like relief. I feed it slowly: the notebook, the tapes, the letters. Paper curls, ink liquefies, sentences deform. I kneel close enough to feel my eyelashes stiffen.

I pull out my phone, open the voice recorder, the red circle blinking against the dark.

“This is Therese Calder for The Crime Line,” I hear myself say, voice steady, broadcast bright. “Tonight, a story about evidence. About what people burn when no one’s watching.”

The wind shifts, smoke in my face. I cough, keep talking.

“Every crime leaves residue—ash, soot, something that resists flame. That’s what interests me. Not what burns, but what doesn’t.”

The tape from the shed lies at my knees. I turn it in my fingers, the plastic casing slick with soot.

“My father taught me that truth and lies burn at the same temperature.”

I toss the tape into the barrel. It melts almost instantly, bubbling like sap. The smell is sweet, chemical. I imagine the sound beneath it—his questions, my answers, our voices layered in heat until they’re indistinguishable.

The fire climbs higher, greedy. My reflection flickers on its surface: hair frizzed, lipstick smudged, face blotched with sweat. The reporter is gone. What’s left looks too much like him.

“You’re listening,” I whisper into the recorder, “to a confession that isn’t mine.”

For a moment, the flames gutter. I lean closer, feeding them pages from my father’s files—each headline, each name, each annotation he’d left on my stories.

“He solved cases,” I say. “I sold them. We both called it justice.”

The barrel roars back to life, swallowing my voice. The recorder grows hot in my hand. I should turn it off. Instead, I drop it in. The hiss is sharp, final, almost satisfying.

The light washes everything out—the snow, the trees, the cabin behind me—until the whole scene looks overexposed, as if I’ve stepped into one of my own broadcasts and can’t find the cut to commercial.

When the last of the flame collapses into red coals, I’m shaking. The air smells of metal and pine and something else, something human.

From inside the cabin, the phone on the table begins to ring. One long tone, then silence.

I don’t answer.

Dawn arrives without ceremony. A smear of white light over the trees, soft as breath. The air outside smells scorched and clean at once—like something ended properly.

The cabin looks smaller now, hunched in the cold. Smoke drifts lazily from the barrel. Inside, the fireplace has gone out, the room littered with grey ash. My phone, still on the table, flashes a dead battery icon. No missed calls. No messages.

I move slowly, gathering what little I brought—the camera, my coat, the cassette’s melted shell. The notebooks are gone, reduced to memory. Every object feels lighter than it should.

When I open the door, the cold hits like a reset. The forest is silent except for the steady drip of thawing snow from the eaves. I walk to the car, brushing frost from the windshield with my sleeve. The burn barrel hisses behind me, the last coals exhaling.

On the passenger seat, the old lighter I found in the shed gleams faintly. I turn it in my hand—engraved initials: R.C. I click it once, watch the small flame waver, then snap it shut. The sound feels final.

I start the engine. The heater groans. The tires crunch through slush as I ease onto the dirt road.

For a long time, I drive without turning on the radio. The silence feels earned. Then, out of habit, I press record on my phone—a reflex as natural as breathing.

“This is Therese Calder,” I say quietly. “Not every story has an ending. Some just stop when you run out of fire.”

I pause, listening to the hum of the tires, the wind against glass.

“What you don’t burn,” I add, “you carry.”

The red light blinks, steady as a heartbeat, waiting.